State-of-the-Art Imaging Technologies Utilized in Tandem Provide Veterinarians a Tool for More Rapid, Accurate and Thorough Diagnoses

Modern equine veterinary medicine paired with monumental leaps in technology and technique are astounding. It wasn’t that long ago when equine veterinarians worked primarily out of their vet trucks, their daily lives resembling the musings of James Herriot, Britain’s beloved country veterinarian. In the 1950s, hoof testers and a stethoscope were about the extent of the daily tools at a horse doctor’s disposal. Today’s veterinary medicine looks wildly different. From innovations in surgical techniques to regenerative medicine and advanced nutrition to rehabilitation, horses are benefiting from a wave of medical progress in the hands of capable and highly-trained veterinarians.

Diagnostic imaging has seen exponential progress and had a significant impact on patient outcomes. While digital radiograph and ultrasound technology changed the shape of veterinary diagnostics, further advancements have had equally (if not more profound) impact. High-quality mobile imaging units, the advent of high-field and standing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), novel cone beam and fan beam computed tomography (CT), as well as nuclear imaging that includes nuclear scintigraphy or “bone scan” and positron emission tomography (PET) have all rewritten the diagnostic playbook, reshaping how veterinarians diagnose and treat equine patients. In short, immense steps forward in imaging technology have allowed veterinarians to obtain real-time views of what’s happening beneath the surface with remarkable clarity. While the imaging modalities themselves have afforded next-level care, the real magic is a combination approach — multimodal imaging — using two or more imaging modalities together for heightened diagnostic accuracy obtained in record speed.

While few equine referral hospitals and universities around the nation offer a full array of imaging modalities, two widely known centers for innovation are among the handful outfitted with a complete menu: Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center in Los Olivos on California’s Central Coast and Rood & Riddle Equine Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. Each facility provides a collaborative approach, with a wide breadth of specialists on staff to examine patients, performing a diagnostic process with exceptional speed and accuracy. Multimodal imaging is playing a key role in this results-driven approach. “(It) allows us to combine different imaging technologies to deliver different answers accurately and quickly,” explains Wade Walker, DVM, DACVS, a board-certified surgeon at Alamo Pintado Equine. While radiography, ultrasonography and endoscopy — commonly used and relatively approachable from a cost perspective — are available at most veterinary hospitals (and from ambulatory practitioners as well), more advanced imaging options are harder to find. MRI, CT and PET carry a greater cost to the client but offer more insight into the root cause of the patient’s problem. “What we can do with multimodal imaging is pick and choose from our menu of options to bring the strengths of each modality to a particular patient. It’s very customized,” says Katie Garrett, DVM, DACVS, a board-certified surgeon and diagnostic imaging specialist at Rood & Riddle. “It’s a real luxury to have everything at your fingertips and be able to recommend the absolute best for whatever that particular horse needs.” The goal of this imaging approach is to establish an accurate diagnosis, which allows for an actionable treatment and recheck plan using the imaging as a benchmark to show if the horse is responding to treatment over time. “Without a good, accurate diagnosis, we’re essentially making an educated guess, and we’re already behind the eight ball because we know there’s very likely something we’re missing,” Dr. Garrett points out.

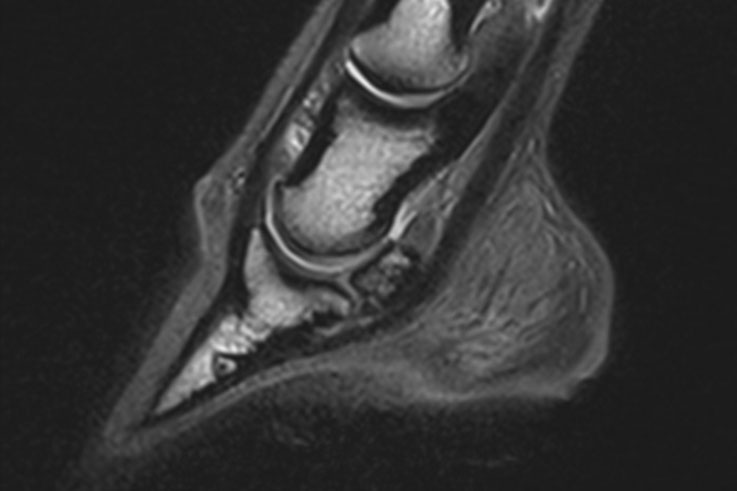

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

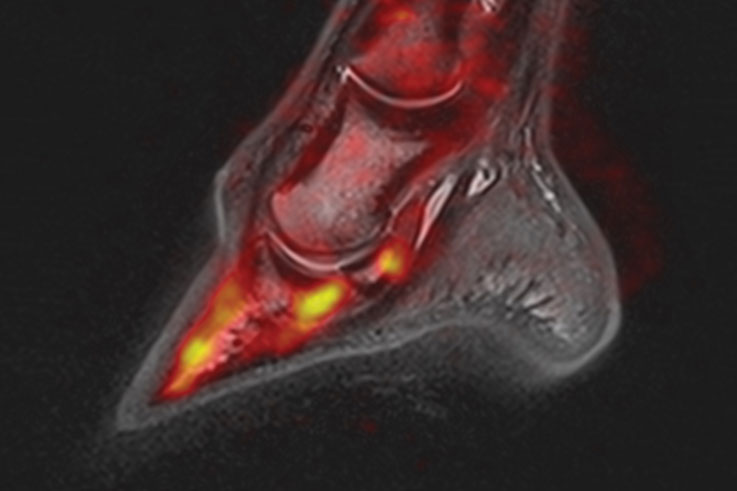

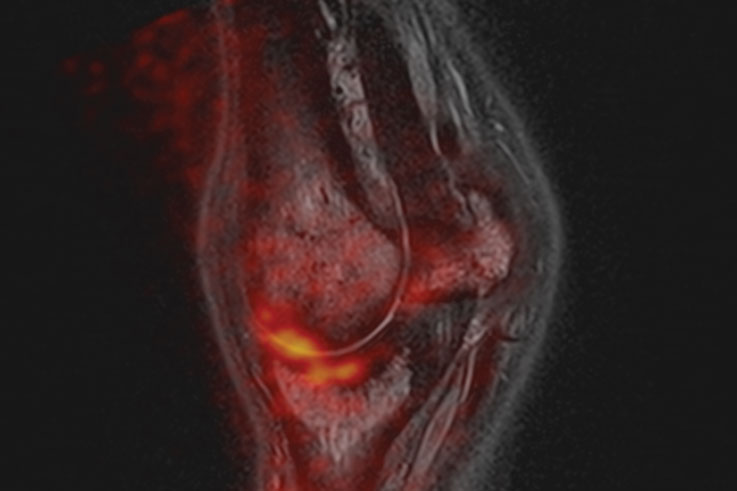

Integrated Multimodal Image

The MRI and PET scans have been superimposed allowing for improved diagnostic accuracy in record speed.

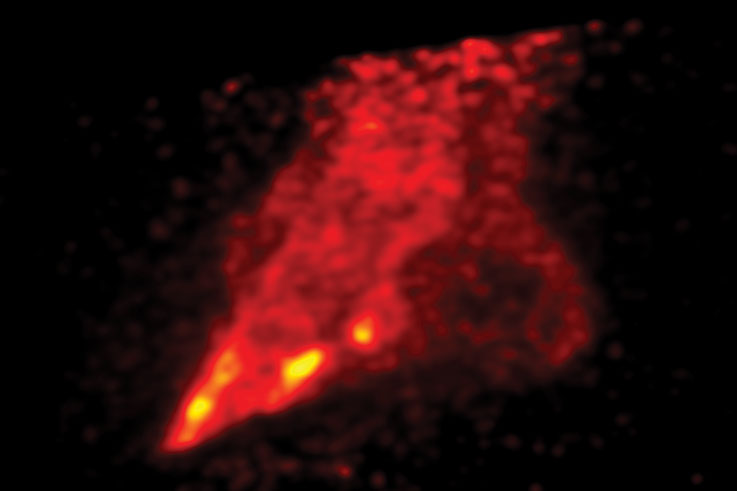

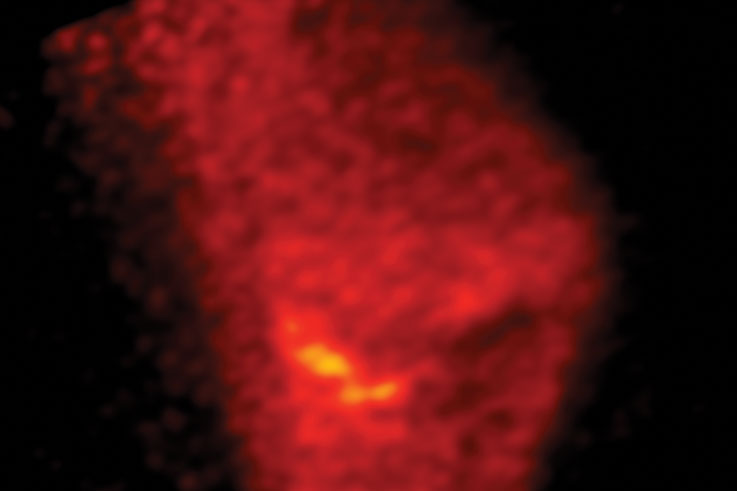

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

The Case Determines the Imaging

With an array of imaging modalities available, seasoned equine veterinarians say there’s no substitute for a good physical examination. “Getting our eyes and hands on the horse for a thorough exam is going to tell us what our next steps are,” offers Troy Herthel, DVM, DACVS, also a board-certified surgeon at Alamo Pintado Equine. Those often include initial nerve or joint blocks, used to better localize the lameness. A neurological examination is often included for prudence, as many neurologic conditions can be disguised as lameness and vice versa, particularly in cervical spine cases. Following those, a veterinarian will turn to diagnostic imaging, with two-dimensional (2-D) modalities often being performed in the field or at the clinic. If the veterinarian suspects the horse is a candidate for one of the more indepth 3-D modalities — MRI, CT or PET — the patient will often be referred to a facility where the technology and expertise are available. “Oftentimes, radiographs and ultrasound are the first line of defense,” explains Dr. Garrett. “They’re available almost anywhere and are less expensive. Many times, those modalities can get us the answer. On the flip side, we see a lot of cases that have already been seen by their primary care veterinarian at home. Since we’re a facility that offers these more-advanced imaging modalities, the case is sent to us to investigate further.”

Dr. Garrett and her team let the patient’s previous history and imaging, and their own examinations, lead them to the advanced imaging choices. “Like most veterinarians, we see a lot of more ‘typical’ appointments,” she explains. “If the horse is a more straight-forward case, we take a few hours, we do our examinations, our initial diagnosis and more standard imaging. The horse goes home with a treatment or rehabilitation plan, and we follow up.” For more involved appointments — including cases where the examination or an unblockable lameness, for instance, suggest advanced imaging — the team will choose modalities based on case specifics. “We might need to move to something like a CT myelogram (with special dye) to investigate a suspected issue in the neck,” offers Dr. Garrett as an example. “One of the major things we’ve learned now in having the ability to capture a CT of the entire cervical spine, is how many horses truly have neck problems. We just simply couldn’t diagnose them with radiographs and ultrasonography. Now we can. An example would be intervertebral foramen stenosis (nerve root problems), these are all coming to the forefront as a potential root cause for lameness that we can’t block. Previously, we were all frustrated by these cases. Now, thanks to CT, we can actually see what’s happening.”

Letting the case determine the diagnostics is a consistent philosophy at Rood & Riddle and Alamo Pintado Equine. “Every case is going to be different,” assures Dr. Walker. “This is why having all the options at hand is important because we’re going to treat an acute soft tissue case very differently than a chronic bone case.” As an example, he details work with a recent patient: “We had a nonunion pastern arthrodesis that came in two years post-surgery because the fracture repair didn’t work. We reoperated, double plated and the surgery went well. We thought the case would progress well, but the horse was still lame. We now couldn’t do an MRI because of the metal plates. Instead, we did a PET scan,” he says of this novel technology offered at Alamo Pintado Equine, one of the only machines of its kind available in private practice. “The PET showed us activity not associated with the surgery; there was a secondary problem. The surgery was a success. Once we treated the horse for the secondary lameness, he became sound.” Dr. Walker’s example highlights the challenges of horses with multiple concurrent issues. While these patients can be frustrating for the practitioner, they’re also ideal candidates for multimodal imaging. “Truthfully, this is most of the horses we see,” says Dr. Walker, acknowledging the number of horses with more than one challenge. “In those cases, the horse comes in and we find the region of pain by blocking the nerves,” he adds. “We then perform a diagnostic like an MRI, but the picture may not always match. MRI is the most-superior soft tissue imaging modality we have, but we then may add a PET scan to the MRI, so we can best see any bone injuries.” While high-field MRI remains the go-to imaging modality for pinpointing the root cause of lameness, Dr. Walker and the team at Alamo Pintado Equine deploy a combination of modalities when the case calls for it, helping to ensure that an accurate diagnosis reveals itself.

Positron Emission Tomography can provide a previously unseen functional dimension that can be overlaid or fused with the structural view provided by MRI, CT and DR.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) utilizes a strong magnetic field (30,000 times as strong as the Earth’s magnetic field) to orient the atoms of the body. By changing this field temporarily, these atoms react and emit radio waves, which are detected and interpreted by a computer to create the image.

While numerous imaging options exist, each brings certain strengths and weaknesses. There’s no imaging modality that will cover every need, but when combined with a multimodal approach, veterinarians can capitalize on the strengths of two or more technologies for maximum clarity as to the root cause of the problem before them. The team at Alamo Pintado Equine offers the following explanations of the available imaging technologies:

2-Dimensional Imaging Modalities

Digital Radiography (DR)

In this cutting-edge technology, digital X-ray sensors are used to capture images of the horse’s anatomy, allowing for quick and accurate diagnosis. The process involves positioning the sensor near the targeted area, which absorbs X-rays passing through, then converts them into an electronic signal. This digital image instantly appears on a video screen and can be manipulated and enhanced by the veterinarian. “Digital radiography is certainly the most used and most tried and true,” says Dr. Wade Walker of Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center. “This modality is a wonderful two-dimensional (2-D) imaging option for bone pathology and subtle abnormalities. It’s not as strong for soft tissue, nor is it a good choice for pathology that hasn’t changed the anatomy or changed the morphology of the bone.” The convenience of immediate image acquisition, the ability to zoom in and out, adjust contrast levels and share images electronically, makes radiographs an invaluable tool for equine veterinarians in diagnosing and treating various conditions.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasounds play a pivotal role in equine veterinary medicine, enabling veterinarians to accurately diagnose and monitor conditions in horses. This non-invasive imaging technique works by emitting high-frequency sound waves that penetrate the tissue and bounce back. These echoes are then captured by a transducer and transformed into detailed, real-time images on a screen. “This modality is good for identifying injuries and inflammation in soft tissue, including tendons, ligaments and muscle,” says Dr. Walker. “Ultrasound is also good in superficial regions but not the right choice for deeper regions.” In addition, ultrasound allows veterinarians to evaluate the reproductive system, including monitoring pregnancies, assessing the health of the fetus and even guiding reproductive procedures. Ultrasonography’s versatility and precision have made it an indispensable tool for equine veterinarians, enhancing their ability to provide accurate diagnoses and tailored treatment plans for their patients.

Nuclear Scintigraphy (Bone Scan)

Bone scan imaging allows veterinarians to identify and assess a wide range of bone and joint conditions. The procedure involves injecting a small amount of radioactive material into the horse’s bloodstream, which is absorbed by the bones. A specialized camera is used to detect and capture images of the radioactive material, providing detailed information about the distribution of bone activity. The ability to perform bone scan imaging without anesthesia is particularly advantageous in equine veterinary medicine. By avoiding the need for anesthesia, veterinarians can minimize potential risks and associated costs during bone scans. Horses can be imaged on an outpatient basis, reducing hospitalization or prolonged recovery periods. The procedure is generally well-tolerated by horses, with minimal discomfort or stress.

Endoscopy

This is a broad category that allows for the minimally-invasive imaging of body cavities using fiberoptics and small cameras. This modality is commonly used to examine a horse’s upper airway from the nasal passage to the trachea, as well as to assess the reproductive, gastrointestinal or urinary tract using a long and flexible endoscope. In orthopedics, small rigid endoscopes can be inserted into a joint, bursa or tendon sheath in order to perform arthroscopy, bursoscopy and tenoscopy, respectively. This allows for a magnified and intimate surgical approach to an anatomic region that can offer insight into structural pathologies that are not always identifiable with other imaging modalities. Better yet, these procedures provide the opportunity for real-time therapeutic intervention, such as the removal of a loose fragment from a joint during arthroscopy or cleaning up a fibrillated tendon during tenoscopy. In addition to its diagnostic and therapeutic benefits, endoscopy is well-tolerated by horses with minimal discomfort and a faster recovery period.

“One of the major things we’ve learned now in having the ability to capture a CT of the entire cervical spine, is how many horses truly have neck problems. We just simply couldn’t diagnose them with radiographs and ultrasonography. Now we can.”

— Katie Garrett, DVM, DACVS

3-Dimensional Imaging Modalities

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is considered the superior diagnostic imaging technology for the diagnosis of orthopedic, soft tissue and head/brain pathology of the horse. MRI utilizes a strong magnetic field (30,000 times as strong as the Earth’s magnetic field) to orient the atoms of the body. By changing this field temporarily, these atoms react and emit radio waves, which are detected and interpreted by a computer to create the image. No radiation is used, and there are no known side effects to the horse. “We’re using MRI to determine what is morphologic and what the physiologic activity is,” says Dr. Walker. “MRI is excellent with soft tissue, but as a stand-alone imaging modality, it’s not as strong with bone.” Alamo Pintado Equine and a small number of other large referral hospitals use a state of the art, high-field (1.5T) Siemens Magnetom Espree. In addition, a low-field standing MRI offers a safe and effective diagnostic tool for evaluating musculoskeletal conditions. This technology allows veterinarians to capture high-quality images of the horse’s limbs while the animal remains standing. The low-field standing MRI provides accurate and detailed information on soft tissue and bony abnormalities.

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT provides thin, cross-sectional images “slices” that are stacked together to create a 3-D image. By using X-rays to produce multiple images, the tool provides more detail than conventional radiographs. CT imaging is especially useful because it can image all types of tissue, clearly showing bone, muscle and blood vessels. One of the more advanced CT tools is the portable BodyTom® full-body, 32-slice CT, used to accurately explore issues within the equine head and neck and to examine complicated dental issues. This CT unit can image fractures and other injuries to bones and joints of the distal limbs and to assist in planning complex surgeries. “This technology is wonderful; it’s essentially a 3-D X-ray using high-quality fan beam technology,” comments Dr. Walker. “There’s also cone beam CT technology, which we’re able to offer in a standing CT for feet and ankles. Both fan beam and cone beam deliver 3-D acquisition, which allows us to obtain multiple planes and examine multi-planar reconstructions.”

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

The powerful nuclear imaging technique commonly used in human medicine is also available to equine patients to better evaluate orthopedic injury. PET scans allow for superior imaging of physiologic bone injury prior to the development of morphologic changes that would be identified using radiographs or CT later on in the progression of disease. PET can be used to further determine the precise cause of lameness when other conventional modalities are unclear or demonstrate multiple lesions of unknown significance. Unlike other available imaging techniques, PET offers a unique ability to quantify the physiologic activity, and therefore severity, of both bone and soft tissue lesions, so healing can be monitored as rehabilitation progresses. PET is synergistic with other advanced imaging modalities as it provides a previously-unseen functional dimension that can be overlaid or fused with the structural view provided by MRI, CT and DR. Together, these modalities provide an unmatched view of the lower limb.

Motion Detection Gait Analysis

Motion Detection Gait Analysis systems — such as Qualysis, the state-of-the-art, 12-camera system found at Alamo Pintado Equine — represent another novel advancement in diagnostic imaging technology. The system allows veterinarians to objectively evaluate a horse’s gait, identifying changes that can be tracked and monitored over time. Using reflectors attached to specific sites on the horse’s head, withers and pelvis, the infra-red cameras detect body movement as the horse jogs through the course, allowing for a quantitative assessment of gait abnormalities that elevate the accuracy of a lameness evaluation.

Advancements Offered by PET Scans

In human medicine, the term “PET scan” is often associated with the detection of cancer metastasis. However, PET is a revolutionary tool for orthopedic diagnostics as well. “In equine medicine, this is a novel technology,” points out Dr. Herthel. “PET can show lesions that precede actual structural changes, then it can also determine activity and distinguish between lesions that are active and a concern we need to address from those lesions that are no longer active and not causing the problem at hand. It does that by highlighting metabolic activity surrounding more active lesions, in contrast to older, more chronic lesions that are just incidental findings.”

One strength of PET technology is it lends itself to working in near-perfect concert with other options. “An ideal pairing would be radiographs and a CT with PET,” explains Dr. Walker. “The radiograph or CT — depending how big the problem is — will reveal morphologic changes, but with PET, you’ll know if those lesions are active or not. The beauty of PET is you can now follow those lesions to see if the activity is improving. Oftentimes, when we see a lesion of the bone on CT, especially where a ligament attaches, the appearance won’t visually look to have changed. However, if we’re able to image it with PET and overlay that with the CT, we’ll see that even though the actual morphology hasn’t necessarily changed with treatment, the activity has decreased, and the horse is healing.”

PET scans are also changing veterinary follow-up. “We can periodically follow that horse and either know that everything’s good (because we’ve created a benchmark), or we can see little problems start to reveal themselves,” explains Dr. Garrett. “That’s when we know, for instance, that we need to back down that horse’s training a little bit. It allows us to make those small tweaks without waiting too long and having to lay the horse off for an extended period. We can get things under control before the point of no return.”

Computed Tomography provides thin, cross-sectional images “slices” that are stacked together to create a 3-D image.

“There’s also cone beam CT technology, which we’re able to offer in a standing CT for feet and ankles,” says Dr. Wade Walker of Alamo Pintado Equine.

Overlapping Imaging for Superior Insight

Multimodal diagnostic imaging’s real superpower is in the ability to overlap complementing imaging for a full view of the problem area. “We can overlap one 2-D imaging modality with another 2-D modality, like a bone scan with a radiograph,” explains Dr. Walker. “With 3-D CT, MRI and PET scanning, we can overlap the images in three dimensions and know exactly where the problem is in space. That’s very important.” Carter Judy, DVM, DACVS, an internationally-celebrated, board-certified equine surgeon at Alamo Pintado Equine, uses a multimodal approach regularly for superior results. “We can not only examine anatomical information, but we can also look at the physiologic information as well,” he adds. “CT is very much about the anatomy that’s there, but it doesn’t give us the physiology of what’s inflamed, what’s remodeling and what’s actively changing in the biomechanical makeup of those structures. PET, on the other hand, really allows us to hone in and identify that what we’re seeing is not only anatomically abnormal but also physiologically abnormal as well.”

“With 3-D CT, MRI and PET scanning, we can overlap the images in three dimensions and know exactly where the problem is in space. That’s very important.”

— Carter Judy, DVM, DACVS, Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

Integrated Multimodal Image

Obtaining a Rapid Diagnosis

While multimodal imaging offers a never-before- seen comprehensive view of a horse’s anatomy and physiology, it’s used with the goal of a quick, thorough and accurate diagnosis. Time is critical when it comes to an injured horse, and obtaining the correct diagnosis quickly directly impacts the success of treatment and rehabilitation. “Our goal is to ascertain a rapid, accurate diagnosis for a good prognosis,” says Dr. Walker. “Lesions that are identified and treated within three months do much better than after three months. That’s been elucidated in literature several times. The faster you discover where the injury is, treat it and start rehabilitation appropriately, the better the prognosis.” In many ways, advancements in diagnostic imaging have offered such a clear view of what the problem is, the challenge is accelerating treatments that address how to fix or improve those problems. That’s where numerous veterinary working groups — the Equine Spine Initiative, for example — and colleges of veterinary medicine, such as the American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, or ACVSMR, are working to establish tested best practices for the treatment and rehabilitation of numerous disease states and injuries.

In some cases, the imaging alone is improving the way certain injuries are treated. “We now know there’s a lot more going on in the foot than simply navicular syndrome,” says Dr. Judy as an example of a structure that has been positively impacted by innovations in imaging. “Thanks to how imaging has evolved, we’ve identified 30-plus structures in the equine foot that can be injured. Without the knowledge of what’s going on and in what specific area, we couldn’t be as effective as we now are at treatment.” Similarly, he has seen imaging technologies change the shape of tenoscopy, a ubiquitous tool in Alamo Pintado Equine’s surgical suite. “In the old days, we may have used four portals (surgical incisions), hoping we would see the whole picture,” he says. “Now, if we image the area with the MRI beforehand, we know exactly where the problem is. That allows us to really focus, make our portals hyper specific and tailor our treatments much more accurately. It’s quicker, much more efficient and better quality with less morbidity.”

Alamo Pintado Equine and Rood & Riddle, and other large referral practices, work hand-in-hand with referring veterinarians to ensure patients are seamlessly handed off to hospitals for advanced imaging (all while keeping the primary care veterinarians actively engaged), then handed back with a clear diagnosis and recommended treatment and rehabilitation protocols. This truly team effort is similar to general practitioners in human medicine referring their patients for imaging or to specialists, then remaining an engaged member of the patient’s care team. “We’re able to offer one-stop shopping, per se,” says Dr. Garrett of what Rood & Riddle, Alamo Pintado Equine and other facilities bring to the table. “The horse arrives, and they’re immediately starting to go through the process,” she says. “They don’t have to wait weeks for the imaging. It’s happening same-day or within a few days.” This can be more efficient in time and cost for clients. “We want clients to go back to their referring veterinarians, and we love continuing to collaborate with them,” adds Dr. Garrett. Collaboration with referring veterinarians, but also within large referral hospitals, certainly augments the effectiveness of this rapid-fire approach to diagnostics. “That collegiality with both the referring veterinarian and amongst the staff at hospitals like ours can be a transformative component,” says Dr. Herthel of the day-to-day inner-workings at Alamo Pintado Equine. “I’m talking to Dr. Judy and Dr. Walker 10 times a day … and it’s to the benefit of the horse,” he says.

“That collegiality with both the referring veterinarian and amongst the staff at hospitals like ours can be a transformative component. I’m talking to Dr. Judy and Dr. Walker 10 times a day … and it’s to the benefit of the horse.”

— Troy Herthel, DVM, DACVS, Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center

The convenience of immediate image acquisition, the ability to zoom in and out, adjust contrast levels and share images electronically, makes radiographs an invaluable tool.

Advanced imaging helps clarify exactly where issues are before surgery.

The Future is Unfolding

Diagnostic imaging has made numerous strides forward in the last half-century, and with it, veterinary medicine has greatly improved its ability to treat. “It’s amazing how far we’ve come in terms of our capabilities, but yet there are still limitations,” points out Dr. Herthel of the need for further innovation. While technology has advanced the profession to new heights, no imaging modality can do it all. While each has strengths and shortcomings, the true breakthrough has come in a multimodal approach, giving the veterinarian an unprecedented view and the capability to diagnose with supreme accuracy and more quickly than ever. “Each modality lets us look at the same structures with different eyes,” observes Dr. Judy. “Sometimes that different perspective delivers a much-clearer idea of what’s going on.” That comfort level has been key in reassuring veterinarians that their diagnosis and treatment plan are on target and in the best interest of the patient. “These diagnostic tools solidify as accurate of a diagnosis as possible,” confirms Dr. Herthel.

As advanced imaging becomes more common across the nation, so does the option to use a multimodal approach. Both Alamo Pintado Equine and Rood & Riddle were two of the first private hospitals in the country to offer high-field MRI on clinic grounds, broadening access to an imaging modality that is considered the top pick when investigating lameness. Up until 2021, there were just three equine PET machines in the U.S. — at Santa Anita Park in December (2019), University of Pennsylvania (2020) and UC Davis (2021) — where today there are roughly 10. As access to MRI, CT and PET expands, patient outcomes will continue to improve. “We’re going to get better results,” Dr. Garrett says confidently, “and hopefully these advanced imaging modalities will continue to become more available and more economical.” The economics certainly come into play. MRI, CT and PET, each offer a more accurate result, yet are a costlier option for the horse owner. Most veterinarians, however, say these technologies are an investment worth making for the client. “In a lot of cases, if we’ve invested time and money on thorough diagnostics, then we can exercise more-targeted treatments knowing that those treatment dollars are being used in the best way possible,” explains Dr. Garrett.

With added clarity comes additional benefits, including the ability to model 3-D implants for complex reconstructions. “Using this approach, we can model an implant for a broken skull, for instance,” says Dr. Judy, who has performed numerous surgeries using 3-D-printed implants produced with multimodal imaging. While this progress is futuristic sounding, it has already paved the way for research investigating further benefits to the horse that can be obtained using a combination approach to imaging. Alamo Pintado Equine and Rood & Riddle are involved in such projects examining the potential of multimodal imaging from injury prevention in Thoroughbred racehorses to better training methods and best practices on which modalities to combine for specific structures and injuries. “This will allow us to gather data and, in turn, gain more information as to further benefits of putting these imaging technologies together,” says Dr. Garrett of the work. “Accumulating anecdotal cases is excellent, but this will put some hard science behind it.”

Ultimately, time marches on, and with it has come rapid progress in technology, technique and understanding related to the horse and how best to not only identify then treat injury and disease, but to prevent them. “This multimodal approach has given us a new set of eyes and different filters with which to look through,” says Dr. Judy of the technology that’s now a part of daily life at Alamo Pintado Equine. “The added clarity has changed how we operate every day.”

Multimodal imaging using advanced technology, all in the skilled hands of expert veterinarians, is shifting veterinary medicine into yet another era of progress that translates to healthier, sounder horses. That is truly what it’s all about. “We all love horses, and they love their jobs,” says Dr. Garrett in earnest. “We want them to be as safe as possible when doing those jobs. This multimodal approach and the research that’s taking place will help keep horses safer; it’ll help me and my colleagues do our jobs better. If we can reduce injury rates for any type of equine athlete with the help of this technology allowing us to identify potential problems and adjust training before there’s an injury, I’m all in. We’re here to take as good of care of them as possible.”