Breaking Down the Three Primary Phases of Soft Tissue Injuries and How They Contribute to Healing Potential

Tendons

Connect muscles to bones or other structures

Ligaments

Connect bones to bones and keep them stable

©PLATINUM PERFORMANCE, INC

ILLUSTRATION BY TOPLINE DESIGN

While it’s often said that a horse owner’s worst fear is colic, arguably, soft tissue injuries — tendons and ligaments in particular — top that list as well. Perhaps in the past, tendon injuries were especially concerning due to their low recovery rate. Horses were often unable to return to their pre-injury performance level and in more challenging cases were euthanized if constant pain and lameness were their prognosis. Today, equine veterinary medicine has progressed dramatically in its ability to not only prevent tendon and ligament injuries but also to diagnose, treat and recover horses that have sustained an insult to these structures. Progress has been achieved through a more-complete understanding of the three primary healing phases and wider and more effective diagnostic imaging and treatment modalities. Three veterinarians who have played a crucial and varied role in advancing the science surrounding equine tendon and ligament injuries are Lisa Fortier, DVM, PhD, DACVS; Stephanie Davis, DVM, cVMA, CERP; and Matt Durham, DVM, DACVSMR. Dr. Fortier is a world-renowned board-certified surgeon and regenerative medicine authority, while Dr. Davis owns and operates the cutting-edge Virginia Equine Rehabilitation and Performance Center where she treats a high number of sport horses who have sustained tendon and ligament injuries, and Dr. Durham — now the senior technical services veterinarian with Platinum Performance® — has spent over two decades treating performance horses at the highest levels of competition as a board-certified sports medicine and rehabilitation practitioner. Together, the trio of equine professionals has amassed deep knowledge on the subject with a frontline perspective on treatment and recovery.

“It’s not just performance horses but all horses and humans that have the same susceptibility to soft tissue injuries.”

— Dr. Lisa Fortier,

Cornell University

Understanding Soft Tissue Injuries

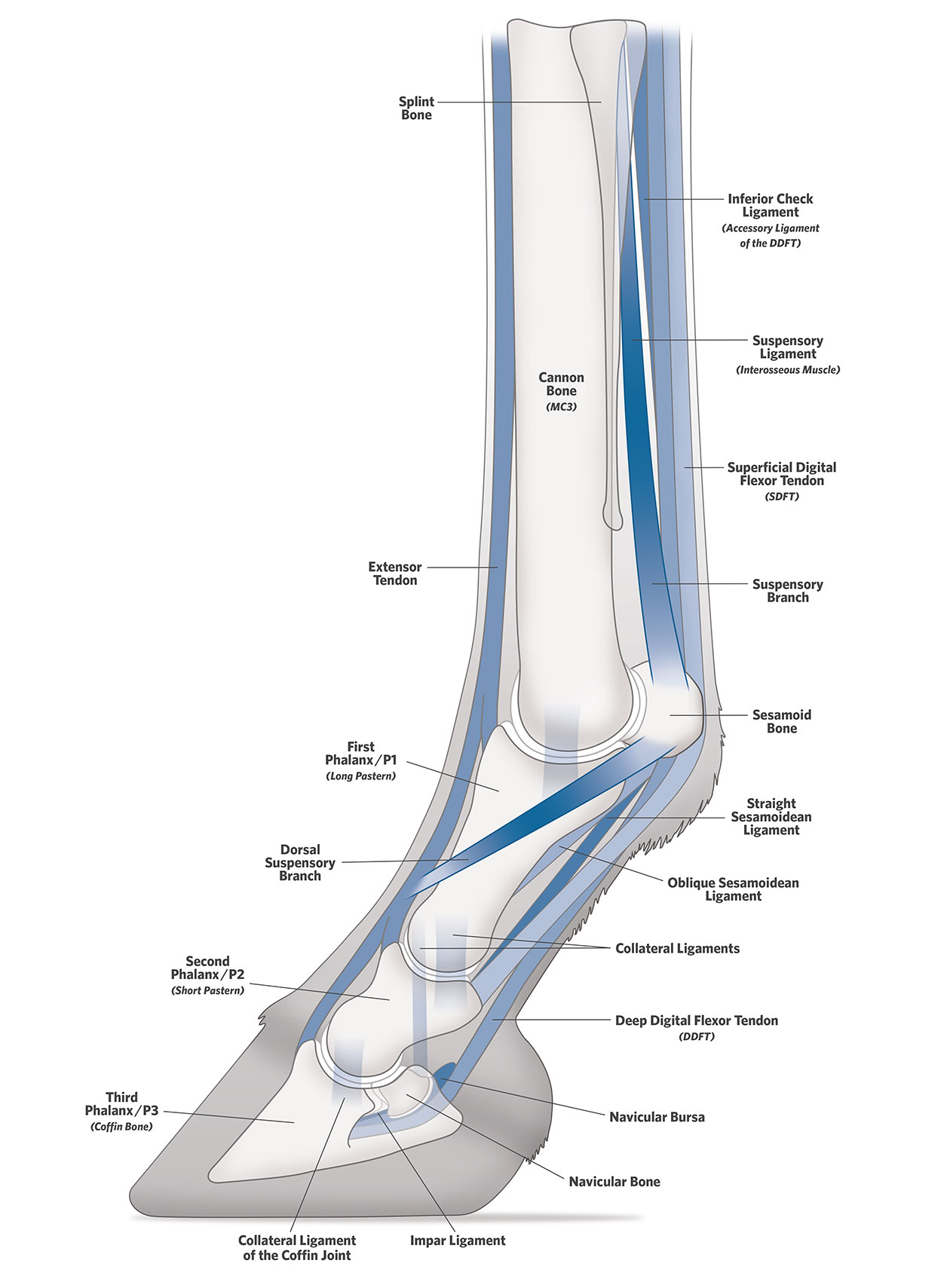

Tendons, which connect muscles to bones or other structures, and ligaments that connect bones to bones and keep them stable, play a key role in a horse’s ability to run, make dynamic movements, turn, pivot, stop and propel. Cartilage, in contrast, is both avascular and aneural (having no direct blood supply and lacking nervous tissue), and covers the ends of bones, absorbing shock in the joint. “It’s not just performance horses but all horses and humans that have the same susceptibility to soft tissue injuries,” highlights Dr. Fortier, who, aside from practicing and educating as the James Law professor of large animal surgery at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine since 1992, was chosen as the 2024 AAEP Frank J. Milne State-of-the-Art lecturer (one of the most significant honors in equine veterinary medicine), lecturing to thousands of veterinarians in December on the very subject of this article. Additionally, she is the Editor-in-Chief of The Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (JAVMA) and The American Journal of Veterinary Research (AJVR) and is the Publications Division Director at the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA).

Horses are natural athletes, and with their speed and agility comes the risk of injury to tendons and ligaments due to several factors that include natural aging, degradative enzyme damage, unchecked inflammation and repetitive strain. “Biomechanically, the superficial digital flexor tendon and the suspensory ligament both take the majority of the load and the strain, so it’s not surprising that they are the most common injuries we see,” explains Dr. Davis of her caseload at Virginia Equine Rehabilitation. “Obviously, we see injuries to the deep digital flexor tendon, inferior check ligament and injuries to both the suspensory branch (the lower portion of the suspensory ligament where it has divided into bundles that attach to the sesamoid bones) and proximal suspensory (the highest portion of the suspensory ligament, where it attaches to the bone).”

Interestingly, not all tendons perform the same role within a horse’s body. “Tendons can be divided into either energy storing or positional tendons,” Dr. Durham explains, “For example, the superficial digital flexor tendon tends to be much more elastic than the extensor tendon. Whereas the role of a collateral ligament, for instance, is not to be overly elastic; it’s much more responsible for stability.” Another example is the marked differences in composition between superficial and deep digital flexor tendons. “The deep digital flexor tendon takes on considerable pressure as the tendon rounds the ‘corners,’ so to speak, at the back of the fetlock, back of the pastern and around the back of the navicular bone. Because of this, there’s a lot more fibroelastic cartilage in the deep digital flexor tendon versus the superficial digital flexor tendon.” Even the orientation, or “crimp pattern,” of the fibers within tendons can vary. “The superficial digital flexor tendon has more springiness to it,” he adds, explaining the normal elastic tendon recoil as the fetlock drops and bounces back at a gallop. While elasticity can diminish with age, veterinarians often see major tendon injuries resulting from “micro-injuries” sustained over time, creating a weak spot in the tendon from repetitive use, which is more susceptible to tearing.

Whether considering a tendon or ligament, injuries to either are the result of damage accrued from stretching and tearing connecting fibers that give the structure its strength. With each structure having a unique role in equine movement, load bearing and performance ability, when injury occurs, it’s critical to maximize effectiveness in each of the three primary healing phases. Tendons and ligaments experience the same phases of inflammation — the goal for all is preventing an injury — but once the damage is there, the objective is shortening each phase of healing. “We’re not trying to eliminate any of the phases; they’re all necessary to effectively regenerate tissue,” says Dr. Fortier. “But shortening them and maximizing our impact in each phase is important.”

“Time is not our friend in the case of soft tissue injuries,” says Dr. Matt Durham. “The sooner these cases get a proper diagnosis, the better chance we’ll have at maintaining range of motion and hopefully getting the horse back to work.”

Phases of Healing

Phase 1:

Inflammation

Lasts about a week

Phase 2:

Granulation

Can last several weeks

Phase 3:

Remodeling

Can last several months to over a year

Three Primary Phases of Healing

Inflammation

“The first phase of healing can last for approximately one week depending on the severity,” explains Dr. Durham. “We’re taught that inflammation is a bad thing, but appropriate inflammation is beneficial. Some of the inflammatory cytokines (messenger molecules of the immune system) that we talk about, like IL-1β, actually signal the healing process.” This initial phase is multi-factorial and nothing if not intricate. “The first thing that happens is neutrophils (white blood cells) come in and soon after macrophages arrive,” says Dr. Durham. “There are two primary phases of macrophages, the M1 and M2 phases (sometimes referred to as the “killer” and “healer” phases that direct removal of tissue or remodeling of tissue respectively). Fascinatingly, we can steer them somewhat, as well as influence what stimulates them.” Ultimately, the goal is never to “turn off” inflammation, but rather, to moderate it using several methods, including steering the free radical activity at play in this phase. “We know that free radicals incite these inflammatory reactions and induce the macrophages to remove tissue,” he says. “That process is normal up to a certain point, but, if it goes too far, then viable tissue can be removed. And that can lead to longer healing time and more inelastic repair.” The target is to optimally manage the inflammatory phase with the goal of setting the stage for normal tissue repair. But how do veterinarians effectively shorten the inflammatory phase while also allowing this necessary natural healing progression to occur?

Knowing that neutrophils are directly responsible for tissue degeneration, veterinarians turn first to rest and the use of cold, in addition to available proven technologies. While most veterinarians agree that cold hosing, or running cold water over the affected area of the horse’s body, does little to reduce inflammation, more applied techniques such as cold wraps, the EQ Press (that provides pneumatic compression therapy to improve recovery time), MagnaWave PEMF (a non-invasive tool to boost cellular metabolism using pulsed electromagnetic fields) and Shock Wave therapy, or extracorporeal shockwave therapy, ESWT, (another non-invasive treatment that uses high-energy sound waves to stimulate natural healing by increasing blood flow) are tools practitioners employ to shorten the inflammatory process while not eliminating it entirely. “If we do see acute inflammation, I’m looking for something reparative that’s not going to produce more inflammation,” emphasizes Dr. Fortier. “This is not a time for corticosteroids.” In the equine practitioner’s toolbox are several orthobiologics options including platelet- rich plasma (PRP), autologous protein solution (APS), autologous conditioned serum (ACS), bone marrow aspiration concentrate (BMAC) and exosomes — extracellular vesicles regarded for their potential anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and pre-regenerative effects; found both as a component of these currently available orthobiologics options and, in the future, in their isolated form. “Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) themselves are often tough in these cases,” she points out. “They’re very anti-inflammatory, but in most cases, we use autologous cells (taken from a horse, cultured, then injected back into the same animal weeks later). That process requires time, which we just don’t have at this phase.” Injection of bone marrow concentrate is an option. This treatment provides fewer cells than in a cultured sample but can be performed at the time of examination.

“We’re taught that inflammation is a bad thing, but appropriate inflammation is beneficial. Some of the inflammatory cytokines (messenger molecules of the immune system) that we talk about, like IL-1 β, actually signal the healing process.”

— Dr. Matt Durham,

Platinum Performance® Senior Technical Services Veterinarian

To prevent the contraction from going too far, veterinarians recommend the horse has controlled activity throughout the granulation phase.

To prevent the contraction from going too far, veterinarians recommend the horse has controlled activity throughout the granulation phase.

Granulation

The second healing phase is granulation, which can last several weeks. In this phase, the body introduces new blood vessels and fibroblasts (cells in the connective tissue that play a critical role in wound healing), forming fragile tissue that fills the lesion at the injury site. This granulation tissue comprises hyaluronic acid, collagen, elastin, proteoglycans and an extracellular matrix. “The body is essentially filling in the gaps during this phase,” explains Dr. Durham. Normally, the majority of a tendon is made up of type I collagen in long parallel bundles, but, in the granulation phase, we have a lot of type III collagen at play. Synthesis of type III collagen and fibronectin is increased in response to tissue injury, with type III collagen contributing by forming a mesh-like matrix network that helps facilitate remodeling. “The key is ensuring this happens to the proper level,” he adds. “If it goes too far, then a scar forms, and that spot essentially becomes inelastic.” Additionally, fibroblasts fill in the space at the injury site. As an example, picture a skin wound, Dr. Durham explains: “In the granulation phase, the open space of the wound fills over with fairly uniform tissue before it then tries to contract and shorten itself (which is more pronounced in severe injuries).” To prevent the contraction from going too far, veterinarians recommend the horse has controlled activity throughout the granulation phase. “Maintaining full range of motion is imperative for long-term success, Dr. Durham says. “Keep the horse moving but do it to the appropriate degree under a veterinarian’s guidance.” During this phase, ESWT, therapeutic ultrasound and class 4 laser are sometimes utilized to encourage the remodeling process.

Granulation tissue has a protective and nourishing role for injured tendons, and while the normal process is imperative to healing, abnormal granulation can be detrimental. Together with the horse owner, veterinarians can manage this to ensure proper growth of granulation tissue and avoid the formation of excess tissue, requiring intervention and extending the healing process. “One of the scary things about granulation, however, is that the horse is often not that painful toward the end of this phase,” Dr. Durham says. “At that three- or fourmonth mark is when it’s easy to overdo activity. The horse is getting bored, and the owner is very often getting fatigued from the rehabilitation protocol. The tendon strength isn’t there yet, but the pain level may be low, so this is where owners have to put the brakes on for that horse. It’s tempting to get them back to work, but don’t do it. This is so important because the granulation phase stimulates the remodeling phase.

If things happen as they should, toward the end of the granulation phase we’ll start to see long-linear fibers forming. Then, we know that there’s some strength coming back to the affected tissue. That’s what we’re looking for.”

This is why the combination of clinical exam and diagnostic imaging is critical to monitor the stage of the healing process.

Remodeling

The third phase of healing is remodeling. “This phase can last several months to over one year and is certainly a more elongated process,” says Dr. Durham. “There’s overlap between all these phases in the way that there’s still a bit of inflammatory reaction going on when granulation starts, and certainly some granulation is finishing as the remodeling phase starts.” A key player in the final phase is type I collagen — the most abundant form of collagen in the equine body and the primary constituent responsible for strength and durability in tendons. Collagen fibrils represent the main tensile element in tendons, and starting from mere millimeters in length, these fibers coalesce to form the crimp pattern referenced earlier. The remodeling phase is when Dr. Davis and her team work to maximize tissue healing through collagen fiber alignment and restoring normal function. Load limiting, or the practice of determining the right amount of load bearing for each patient, is crucial in achieving both. “We do more loading than most, even as early as the granulation phase, to help support that range of motion,” says Dr. Davis. “That controlled, progressive loading is incredibly important, and the way we accomplish it safely — especially in earlier phases of healing — is with a research-backed device known as the TendonPro Dynamic Support System (DSS), a newer device that allows for fetlock support and safe, proactive exercise during healing,” she explains. “Using this boot, we can control how much load the tendons will endure. It provides the opportunity to increase the gait and incorporate some trot, which increases the load while keeping the horse from a peak load that could overstrain them.” The goal is a happy medium, where the horse is challenged with enough load to act as a vital stimulus for tenocytes to repair correctly, yet not to the point where it exceeds what the injured tissue can bear.

“That controlled, progressive loading is incredibly important, and the way we accomplish it safely — especially in earlier phases of healing — is with a research-backed device known as the TendonPro Dynamic Support System (DSS), a newer device that allows for fetlock support and safe, proactive exercise during healing,” Dr. Stephanie Davis explains.

“Using this boot, we can control how much load the tendons will endure. It provides the opportunity to increase the gait and incorporate some trot, which increases the load while keeping the horse from a peak load that could overstrain them.”

— Dr. Stephanie Davis,

Virginia Equine Rehabilitation and Performance Center

Ultrasound is often the first-line diagnostic imaging tool for suspected tendon or ligament injuries.

Ultrasound is often the first-line diagnostic imaging tool for suspected tendon or ligament injuries.

Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic technique and technological innovations are a game-changer in soft tissue injury healing. Whatever the stand-alone diagnostic modality or diagnostic stack chosen, a running theme is “time is of the essence.” “Time is not our friend in the case of soft tissue injuries,” says Dr. Durham. “The sooner these cases get a proper diagnosis, the better chance we’ll have at maintaining range of motion and hopefully getting the horse back to work.”

Ultrasound is often the first-line diagnostic imaging tool for suspected tendon or ligament injuries. “Most of us have an ultrasound (device) on our truck, and it can be a very accessible and cost-effective method for the client,” points out Dr. Durham. While some imaging characteristics of more traditional ultrasound are, in fact, superior to other modalities for soft tissue injuries, there is a novel and more-advanced ultrasound tool available. Dr. Davis and her team have been early adopters of UTC, or ultrasound tissue characterization, a technology that combines hardware and software to create a 3-D image of tendons and ligaments to assess their structure and fiber composition, mostly in the distal limb. “We’ve been supporting traditional ultrasound with the use of UTC because it gives us the ability to see the state of the fibers and categorize them into four echo types: type one (green) are healthy, flexible fibers; type two (blue) are less flexible/organized fibers that can be part of the granulation phase but can also appear in excess in scar tissue; type three (red) are strained fibers present in lesions; and type four (black) is definitively the hole. No fibers are there,” explains Dr. Davis. While UTC can match traditional ultrasound in many ways, the color schematic can give incredible insight into the state of the fibers and what amount of load bearing they’re ready for. “It is also extremely valuable during rehabilitation to tell us whether the injury site, or that gap in tissue, is filling correctly with the prescribed amount of mechanical stimulus and loading,” she adds. Beyond traditional ultrasound and UTC, there are numerous diagnostic imaging modalities used alone or in tandem to help properly diagnose, then follow the healing progression of soft tissue injuries, including MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), CT (computed tomography) and PET (positron emission tomography).

Ultrasound tissue characterization (UTC) is a technology that combines hardware and software to create a 3-D image of tendons and ligaments to assess their structure and fiber composition.

“We’ve been supporting traditional ultrasound with the use of UTC (ultrasound tissue characterization) because it gives us the ability to see the state of the fibers and categorize them into four echo types: type one (green) are healthy, flexible fibers; type two (blue) are less flexible/organized fibers that can be part of the granulation phase but can also appear in excess in scar tissue; type three (red) are strained fibers present in lesions; and type four (black) is definitively the hole. No fibers are there.”

— Dr. Stephanie Davis,

Virginia Equine Rehabilitation and Performance Center

Rehabilitation Strategies

With more concrete and proven equine rehabilitation protocols, the stage is set for immense progress. “If we can get to the horse in the first two phases of wound healing, then we have a much better shot than we ever have before,” says Dr. Davis. As horses enter her rehab facility, she and her staff have a protocol that each case works its way through before being customized. “Each horse is given a UTC scan to give us a solid baseline understanding of where their tissues are at,” she says. “We’ll then create a 30-day program that includes controlled loading using the TendonPro DSS boot.” Twice a day horses will work on the dry treadmill; its variable speed and incline are designed to improve the animal’s strength, flexibility, stamina and balance. The straightness and controlled rhythm it affords far surpasses a hand walk. “When we hand walk them, they’re looking around. Their shoulders and hips are going different directions, and there’s not a lot of intention to their pace,” explains Dr. Davis. “With the dry treadmill, we can set the pace and the straightness while they wear their boot to ensure we control loading and protect from overstrain.” Where appropriate, certain cases will also be lunged at a trot four to five times a week even in the granulation phase, although the amount of time the horse is allowed to trot can vary widely. “If we’re dealing with a severe superficial digital flexor tendon tear, they may trot for 10 seconds one way and 10 seconds the opposite way,” she says. “It can be a short amount of time, but most importantly, they got their exercise. And, that trot time will progressively increase over a 30-day period.” Also in that schedule, Dr. Davis is using the facility’s vibration stall, PEMF, class-four laser, acupuncture, kinesiology tape and other supportive tools that can be effective. “At the 30-day point, we’ll reevaluate using UTC to see where we’re at in terms of the tissue healing and remodeling,” she explains of how progress is gauged. The strength of the program is revealed in the sum of its parts rather than one standalone therapy, in addition to the amount of attention and activity the horses see from Dr. Davis and her team. “We get them out of the stall maybe six or seven times a day, so they’re quite busy doing all the different therapies, walking or exercising,” she adds. “That mental aspect of avoiding boredom is important, but it can be a lot of work for the horse owner. Larger, more focused facilities like ours can alleviate that for them; we can put that time and effort in that’s required to bring the horse back.”

The science of equine rehabilitation has progressed dramatically from a loose collection of unproven exercise options to a researched and tested practice with the capability to achieve outstanding results. The most significant advancement, however, may be the simplest. “Rehab does not equal rest,” says Dr. Durham. “To do it right, it’s a lot more work than most people realize. That’s why facilities like Dr. Davis’ are so valuable. There’s a dedicated and educated team there to make sure things are being done just so and consistently. They’re stimulating remodeling and encouraging full range of motion, while also entertaining the horse and preventing that boredom that can be their nemesis.”

“A lot of riders don’t consider just how important metabolic health is in the horse and how metabolic dysregulation can be detrimental to tendons and ligaments.”

— Dr. Lisa Fortier,

Cornell University

A Comprehensive Approach to Recovery

With advancements in imaging, treatment and rehabilitation strategies, tendon and ligament injuries have a more positive prognosis than ever. Healing isn’t linear, however; it’s a journey that takes commitment and a multi-faceted plan of attack. “It’s nutrition, farriery, post-surgical rehabilitation; it’s all of it together that makes the difference,” says Dr. Fortier. Virginia Equine Rehabilitation, meanwhile, deploys a nutrition plan for every equine patient. “We keep things simple but effective,” Dr. Davis says. “We know a forage-first diet is ideal. Our horses are fed twice per day and grazed daily as well. Fresh grass in a natural grazing environment is obviously best, then good quality forage in the form of hay is secondary. Aside from forage, we feed Platinum Performance ® GI or Platinum Performance® CJ and, beyond that, we support the gut. These horses are busy. They’re undergoing treatments, and it’s a new environment. We incorporate two formulas to support the pH of the stomach and the gut microbiome: Platinum Gastric Support ® and Platinum Balance® respectively. Research has also shown that certain wavelengths lower resting cortisol levels, so we also play soothing music for them 24 hours per day to mediate stress.”

Doubling down on the importance of nutrition in the recovery process, Dr. Fortier has long promoted targeted nutrition for not only the horse’s overall health and in support of their joints, tendons and ligaments but also for their metabolic state. “A lot of riders don’t consider just how important metabolic health is in the horse and how metabolic dysregulation can be detrimental to tendons and ligaments,” she says. “I’ll walk through a client’s barn, and they’ll tell me, ‘My horse is too thin.’ And nearly every time I answer with, ‘Your horse is perfect.’ I truly believe that, as veterinarians, we should be testing insulin on the same schedule as when we vaccinate them, especially with stall-side insulin tests now available. Do it twice a year, and don’t let your horse become overweight. Also, make sure their nutrition and any deficiencies are addressed, including focusing on those omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants, along with vitamin D and selenium if they need it. They don’t require a million supplements. Choose the right formulas, keep things simple and that’s typically the best way to go. My personal horse, Franklin, is on good quality forage and Platinum Performance ® CJ, and that’s basically all he gets. Most horses don’t need more than that.”

While preventing tendon or ligament injury is the goal, horses as athletes are always at risk of injury. Providing the right building blocks to support overall health along with targeted nutrients for joints, tendons and ligaments is an ideal strategy for healthy, sound athletes and to support injured horses throughout the healing phases and beyond. “Think of this as phase zero,” says Dr. Durham. “It’s taking a preventive approach to avoiding these injuries in the first place. And that starts with the development of horses and monitoring them while they’re working, sound and healthy. It’s so important that we develop healthy babies and provide access to pasture as they grow, if at all possible, which makes for stronger tendons and bones and better core stability and proprioceptive ability, meaning their balance and their ability to know where their legs are in space. There are so many things that we need to do to build the horses from the ground up, including nutritionally, but also just in terms of how we’re managing them, their conditioning program and working with their veterinarian when the horse is sound, not just when they’re injured.”

Regular wellness checks and soundness exams are mainstays, allowing the vet to feel tendons, flex the horse and watch them move under saddle. This approach helps establish a baseline that often makes it easier to detect a looming injury or small irregularity sooner. “As veterinarians, we don’t want to start from a catastrophic phase,” says Dr. Durham. “Once there’s an injury, we’ve got a much bigger challenge on our hands. Prevention is obviously ideal, and we can work with clients to do as much as possible on that front. When an injury does occur, that comprehensive approach is where we can achieve the best results — so much better than we ever have previously.”

Where tendon and ligament injuries were often career ending, the prognosis today is considerably more positive. A rider can rest easier thanks to trailblazing practitioners making headway in a research environment, daily practice and well-equipped rehab facilities. Through careful management of the healing process, equine tendon and ligament injuries stand their greatest chance yet of healing completely, with the horse returning to work comfortable, sound and with a minimized chance of reinjury.

Amie Grohl, co-owner of Premier Equine Center, an Oakdale, California-based veterinary-guided equine rehabilitation facility, is pictured using a class-four laser and the Bemer PEMF blanket on a rehabilitation case.

In the Platinum Podcast

Tendon Issues and More

Explore tendon injuries, including the three primary phases of healing and strategies for optimal recovery. Hear about the latest rehabilitation techniques and advancements in research and technology.

Listen Now