Dr. Amy Polkes is an equine veterinarian board-certified in internal medicine. As a referral veterinarian, she provides specialized services in complex cases. She’s well-versed in equine cardiology and is equally impassioned about its importance in veterinary medicine.

Equine Internal Medicine Specialist Dr. Amy Polkes Discusses Conditions Affecting the Equine Heart, Their Impact on Performance and Safety, and Her Work to Increase Awareness of Cardiac Health in Equine Athletes

At first glance it seems obvious that maintaining optimal cardiac health in the horse is a given. We fully grasp the importance of a properly-functioning heart for ourselves, as humans and athletes and, of course, we see the same for our equine counterparts. As it turns out, however, our approach to fully understanding, maintaining and addressing our horses’ cardiac health has simple improvements that can be implemented for significant impact.

“I’m passionate about this area of veterinary medicine because, to varying degrees, it touches every patient we see.”

— Amy Polkes, DVM, DACVIM, Equine Internal Medicine and Diagnostic Services

Taking Knowledge to Heart

As with most things, there’s power in knowledge. As riders, together with our veterinarians, we can be proactive in managing our horses’ cardiovascular health to ensure that they are fit and able to optimally perform with us safely on their backs. Dr. Amy Polkes, who owns Equine Internal Medicine and Diagnostic Services (EQUINE IMED), an ambulatory specialty practice in the Virginia/ Maryland region, is an equine veterinarian board-certified in internal medicine. As a referral veterinarian, she provides specialized services in complex cases elevated to her by area colleagues. She’s well-versed in equine cardiology and is equally impassioned about its importance in veterinary medicine. She’s a regular speaker at equine veterinary meetings and conferences across the country, delivering her wealth of knowledge and expertise on the subject to peers, and educating on the gravity of cardiac health in horses and how it affects their everyday work as athletes. “I’m passionate about this area of veterinary medicine because, to varying degrees, it touches every patient we see,” she says.

While cardiac function is vitally important to a horse’s ability to perform, what conditions exist and how are they identified and treated? Dr. Polkes offers a critical set of specialty skills, and she’s the first to point out that specialists work with the patients’ primary-care veterinarians to deliver comprehensive care. “Patients are referred by equine veterinarians who are elevating a case that requires more specialized diagnostics and expertise,” she explains. “I complete my workup, then continue to work together with that patient’s primary veterinarian to ensure we are providing proper follow-up care.” It’s a fluid, professional and cordial relationship that allows for close monitoring and engaged patient care, seamlessly handed off from veterinarians to specialists and back again.

“If you put the stethoscope on and listen quickly, you might catch a murmur that’s happening with every beat, but in an arrhythmia, it doesn’t necessarily happen with every beat. If you’re not listening for a full minute, it can be easy to miss something that may not happen on the second beat, it may happen on the seventh beat.”

— Amy Polkes, DVM, DACVIM, Equine Internal Medicine and Diagnostic Services

Diagnostics

Establishing a clear picture of a patient’s cardiac health begins with the basics. Dr. Polkes strongly advocates for integrating a cardiac exam into biannual wellness checks (at a minimum), allowing the veterinarian to clearly listen to the heart and pick up on most common murmurs, sounds produced by the turbulent flow of blood through the heart, that can indicate a next step based on severity. “One really important thing that I always tell veterinarians is that you have to listen for a full minute and on both sides of the chest,” she advises. “If you put the stethoscope on and listen quickly, you might catch a murmur that’s happening with every beat, but in an arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat), it doesn’t necessarily happen with every beat. If you’re not listening for a full minute, it can be easy to miss something that may not happen on the second beat, it may happen on the seventh beat.”

When it’s determined that a second opinion is necessary, a board-certified internal medicine specialist with advanced cardiology training is called in. “The first thing we’re going to do is, of course, listen,” she says of the moment she begins a case. “We then perform an ultrasound exam with specialized portable equipment to look at the structure and function of the heart.” Here, she listens, watches blood flow, takes measurements and begins to establish a picture of the patient’s cardiac function. “From there, depending on what we see, we’ll decide if further diagnostics are needed, and that can include an ECG (electrocardiogram) and an exercising ECG to check the horse’s cardiac function under saddle and in work.” Understanding the horse’s cardiac function at rest and while exercising is a key piece of the diagnostic puzzle and can help distinguish between an actionable issue and one that doesn’t require intervention. “As an example, a horse may not have an arrhythmia at rest, but if they have an enlargement of one of their chambers — their left atrium, left ventricle, right atrium, anything like that — I can pick up on that while they’re exercising,” Dr. Polkes explains. “That’s when an exercising ECG becomes important to establish what’s going on and if the horse is truly safe to ride.”

The images produced from an echocardiogram, or cardiac ultrasound, are surprisingly clear. ECG leads are attached to the horse’s skin while standing to observe the electrical activity of the heart, as Dr. Polkes compiles information on heart rate, blood flow and size of cardiovascular anatomy. “We look at every valve, we look at standard cardiac measurements and anything that we may be concerned about,” she explains of her process. “If we determine that we need to do an exercising ECG, there are a few different ways to do that using different types of cardiac diagnostic equipment. The Televet™ telemetric ECG is one of the most common and what I typically use for an exercising ECG. The ECG leads are placed to see the horse’s ECG in real time while performing an exercise test to determine if their heart rate is appropriate for every level of exercise and if there are any arrhythmias of concern.” In some cases, the data is clear and determines that the case isn’t an immediate concern but should be watched. Other cases require further analysis while still others show an immediate and pressing concern for rider safety due to the severity of the arrhythmia. Watching Dr. Polkes perform an exercising ECG is a wonder. The horse goes about its normal work, while sensors placed beneath the saddle relay real-time information to a tablet in her hands just feet away from horse and rider. It’s a true combination of art, science and technology melding seamlessly in the field.

In addition to advanced diagnostic imaging and technology, Dr. Polkes and her fellow specialists rely on good basics to complete the picture of what’s happening with each individual case. “I want to know pretty much everything: what the horse is being fed and supplemented; which medications they’re receiving; any changes the rider has noticed; if the horse has had a recent surgery and so on,” Dr. Polkes details. “It’s all relevant.” This information, combined with the horse’s history and a thorough cardiac workup, help to accurately diagnose and grade a murmur, as well as pinpoint specifics related to an arrhythmia.

Grading Equine Cardiac Murmurs

Murmurs Grade 2 or Higher Call for Advanced Diagnostics

- Grade 1: Extremely soft-sounding murmur only heard in a very quiet room with a stethoscope.

- Grade 2: Readily heard yet still soft-sounding murmur.

- Grade 3: Louder murmur that has a moderate range of radiation.

- Grade 4: Louder murmur that has a wide range of radiation.

- Grade 5: Very loud murmur easily heard with a palpable thrill, or vibration.

- Grade 6: Very loud murmur heard off the chest wall with a thrill.

Arrhythmias

- Supraventricular: Begins in atria

APCs (atrial premature contraction), atrial fibrillation, atrial tachycardia/flutter - Ventricular: Begins in ventricles

VPCs (ventricular premature contraction), ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation - Bradyarrhythmia: Slow heart rhythms

Heart block, sinus bradycardia - Tachyarrhythmia: Elevated heart rhythms

Sinus tachycardia, atrial tachycardia/flutter, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation

The Murmur

There are numerous similarities between the horse and its rider when it comes to equine veterinary medicine, and that includes cardiology. One such instance is heart murmurs. They’re quite common in horse and human, and although horses have a dramatically-larger heart, the general mechanics are parallel. When performing a cardiac auscultation — listening to the heart through a stethoscope — as part of her first line of diagnostics, Dr. Polkes is attuned to the subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) nuances of the heart. While murmurs are common, not all of these disruptions in the normal blood flow of the heart are created equal. “A murmur occurs when blood is supposed to go in one direction but instead it goes in another direction, and you can hear that vibration with the blood flow,” Dr. Polkes simply explains.

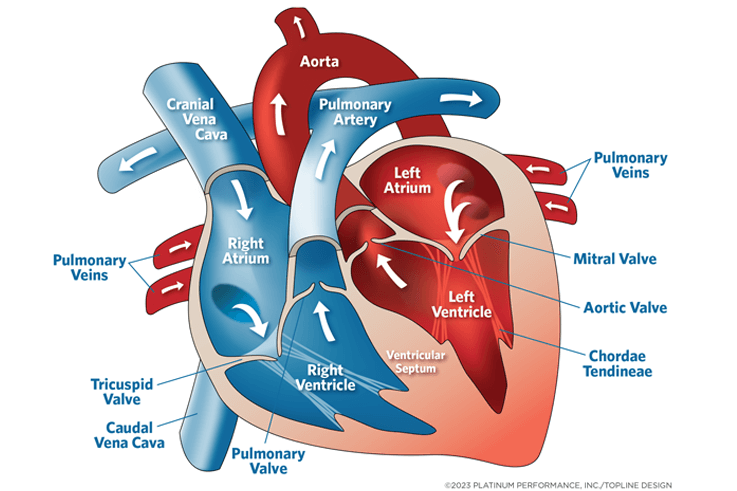

There are two general classes of murmurs. “Systolic murmurs occur during the pumping phase of the heart cycle, whereas diastolic murmurs occur during the filling phase of the cycle,” she says. The first step an equine cardiologist takes is classifying the murmur as occurring in the pumping or filling phase. Next, she works to determine the location of the murmur. The left side of the chest will indicate the pulmonic, aortic, or mitral valve; the right points to the tricuspid. “With the horse being so large, if there’s a problem occurring on the right side, you often won’t be able to hear it from the left,” says Dr. Polkes of why it’s necessary to listen for a full minute on both sides of the horse.

Next, she classifies the murmur as functional or pathologic. Functional murmurs are a manifestation of normal blood flow and include vibrations related to the ejection of blood (systole) or rapid ventricular filling (diastole). There’s not a problem with the valve in either of these cases, but the rapid blood flow causes turbulence leading to the murmur. Functional systolic murmurs can be heard most commonly in the horse starting after S1 (the first heart sound; a single pulse sound as the mitral and tricuspid valves close) and ending before S2 (the second heart sound, heard when the aortic and pulmonic valves close). According to Dr. Polkes, these murmurs occur in nearly twothirds of normal horses and are related to the large size and volume of blood flow through the equine heart. Horses in these cases most often lead normal lives without safety concerns or much further investigation. Functional diastolic murmurs can also occur, but are less common, exhibiting a subtle “squeak” over the mitral valve or the tricuspid valve.

Pathologic murmurs represent abnormal blood flow and most commonly indicate incompetent valves in horses, while VSD (ventricular septal defects) and other developmental defects can also occur. Stenosis, the narrowing of valve openings causing restricted flow, while common in people and dogs, is rare in horses. In the case of pathologic systolic murmurs, they’re mostly seen in horses with mitral or tricuspid regurgitation, where blood leaks back through the valve into the chamber from which it came. Think of blood flow as a one-way street; traffic needs to keep moving in its intended direction and shouldn’t be reversing as normal valves work as one-way gates preventing backflow (regurgitation). It’s that portion of blood leaking backwards in reverse that can cause pathologic systolic murmurs.

Pathologic diastolic murmurs can also occur. Here, the distinct sound can be picked up after S2 when listening to the horse with a stethoscope. Because these occur during the longer filling phase, these murmurs are typically longer and can sometimes have a dramatic “dive-bomber” sound. The associated differential diagnosis in these cases most commonly points to aortic insufficiency.

After determining the type, the intensity of the murmur is graded. “A grade one murmur is extremely soft sounding, whereas a grade six has a palpable thrill, where we can put a hand on the horse’s chest and feel the vibration of the heart with the blood flow. Any murmur that’s a grade two or higher calls for more advanced diagnostics,” details Dr. Polkes of the six-point scale.

Passionate about equine cardiology, part of Dr. Amy Polkes’ focus is to help prevent sudden death incidences where the horse suffers a catastrophic cardiac event and puts its rider at risk.

The Consequence of Murmurs

Severe murmurs can lead to numerous cardiac problems for the horse, including poor performance, arrhythmias, heart failure and sudden death. “When you have blood flowing in the wrong direction, you can get an enlargement of the heart,” says Dr. Polkes. “This enlargement is where all the electrical conduction is in the heart muscle wall. It stretches and can cause abnormal rhythms. It’s these arrhythmias that are probably more dangerous than the murmur itself.” In addition, more severe murmurs can cause heart failure, which is deadly for the horse as well as the rider when this occurs. “It’s not just that the blood is flowing in the wrong direction, and we have a murmur,” Dr. Polkes emphasizes. “It is what it does to the heart that will eventually cause the major problem. I can listen to a murmur, but until I look at it with an ultrasound and do an echocardiogram, I can’t really tell exactly what’s going on, what’s causing the blood flow issue, and what the cardiac chamber sizes are.” It’s critical that cases with a murmur are referred to a specialist to establish specifics and a follow-up plan to protect horse and rider.

Equine Heart

“If we don’t listen, we’ll never know.”

— Amy Polkes, DVM, DACVIM, Equine Internal Medicine and Diagnostic Services

Arrhythmias

Arrhythmias (irregular cardiac rhythms) are caused by a disruption in the electrical conduction of the heart and can develop as isolated incidents or as a secondary occurrence related to another factor such as structural heart disease, metabolic or endocrine disorders, systemic inflammation, hypotension, hemorrhage, anemia and ischemia, autonomic changes, toxicity or drug side effects. “These arrhythmias are what can lead to the devastating sudden death events,” says Dr. Polkes. Properly diagnosing arrhythmias is the key to discerning which horses are a concern and those that simply need to be monitored. An irregular heartbeat or murmur are the first clues that the equine cardiology specialist needs to investigate further.

Common arrhythmias that specialists encounter can include a second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, high-grade AV block, atrial fibrillation, atrial premature contractions (APCs), ventricular premature contractions (VPCs), ventricular tachycardia and sinus tachycardia. Second-degree AV blocks are characterized by a normal to low heart rate and irregular rhythm with a repetitive pattern. This type of arrhythmia will likely disappear when physical activity and sympathetic tone are increased. “These horses indeed have a low heart rate; they will drop a beat. But if you take that horse and just walk them up and down the aisle, you raise their heart rate high enough that this arrhythmia will go away instantly. That tells us we’re hearing a second-degree AV block, and it’s very normal. We hear these all the time,” Dr. Polkes confirms. With a high-grade AV block, equine patients experience more than two consecutively-blocked P waves observed in the ECG, indicating an abnormal rhythm. “These horses are dropping more than one beat at a time. They’re having a beat, then going a long period of time without another one,” Dr. Polkes cautions. “This can cause what we call a syncopal, or fainting episode. If that’s happening while they’re standing there, that’s very different than if it’s happening while they’re being ridden.”

Another common arrhythmia is frequently seen in human medicine as well. Atrial fibrillation — including paroxysmal and lone atrial fibrillation — tops the list in terms of those that affect equine performance. It’s signified by a sound that combines premature beats and long pauses, although the resting heart rate is typically normal. “Horses have very large atria and a large heart in general,” Dr. Polkes explains. “We can see atrial fibrillation caused by a variety of things but especially when the horse has a murmur and is experiencing blood flow leaking back the wrong way.” These horses are examined critically for relevant murmurs. “In these cases, every time blood flows from the atrium into the ventricle, they’re having leakage of blood going back into the atrium,” she says. “This process will enlarge the atrium and over time as the atrium gets bigger and bigger, you can have a rhythm disturbance, and the patient can go into atrial fibrillation.” AFib can be a secondary occurrence resulting from outside factors, such as anesthesia and electrolyte imbalances, products high in iodine or kelp, or various types of prescription drugs, just to name a few culprits.

Next in the lineup of common equine arrhythmias is an APC, or atrial premature contraction. This results from extra heart beats conducted from the atria and is usually detected during auscultation as premature beats that interrupt an otherwise normal rhythm. While APCs aren’t typically responsible for poor performance in horses, they are a concern due to their potential to incite atrial flutter or atrial fibrillation. “We can sometimes see APCs after exercise, but it’s not normal to hear a lot of them. Instead of the horse’s heart beating regularly, there’s an extra little beat that comes in. We’re not always sure why it happens, but there can certainly be a problem in the atria with scarring or something that’s causing that beat to reroute,” Dr. Polkes says.

In contrast with APCs, ventricular premature contractions, or VPCs, have a telltale extra heartbeat conducted from the ventricles in the lower portion of the heart interrupting an otherwise normal rhythm.

“VPCs are a bit more concerning as they’re more related to some of the sudden death events that we see,” says Dr. Polkes of why she takes the diagnosis and evaluation of these patients so seriously. “Horses can get VPCs from enlargement of the left ventricle, although the most common cause would be from aortic regurgitation. We tend to see aortic regurgitation more frequently in older horses but not exclusively. This would be classified as a diastolic murmur, in that every time blood is supposed to go from the left ventricle out through the aorta, it’s coming back into the left ventricle, and over time, there’s an enlargement.” Dr. Polkes will sometimes see a few scattered VPCs on a normal ECG, but when greater numbers point toward the enlargement of the left ventricle she mentioned, the horse may be deemed unsafe to ride.

Last in the line of common equine arrhythmias are ventricular and sinus tachycardia. “VT, or ventricular tachycardia, is an abnormal rhythm caused by three or more repetitive or linked VPCs ventricular premature contractions,” Dr. Polkes explains. “Auscultation of VT is characterized by a rapid, usually regular rhythm, with variable intensity and often booming heart sounds.” The biggest concern is that VT can occasionally convert to the typically-fatal ventricular fibrillation. On the other hand, ST, or sinus tachycardia, is seen as a heart rate above 60 beats per minute. Here, every P wave, which represents atrial depolarization on an ECG, is followed by QRS, a combination of the Q, R and S waves on an ECG, or ventricular depolarization. This can be a normal physiological response to exercise, pain, stress and more. “Sinus tachycardia is a normal beat, but it’s happening very fast,” Dr. Polkes points out. “Sometimes that can be from external factors like pain, colic or dehydration. There’s not necessarily something wrong with the electrical conduction of the heart, but it’s simply beating too fast. The most important thing is understanding and identifying what exactly is happening.”

Determining Safety

Dr. Polkes is undeniably passionate about equine cardiology, and part of her focus is to help prevent sudden death incidences where the horse suffers a catastrophic cardiac event and puts its rider at risk of extreme injury or death. “The ACVIM (American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine) came up with a consensus statement drafted by some of the most prominent cardiology experts in our field,” Dr. Polkes says. “Although this was almost 10 years ago, it’s still very relevant. It walks through the cardiac issues we’ve discussed and explains how veterinarians determine if the horse is safe to ride.” There’s of course no clear-cut answer in every case, but equine cardiology specialists carry the burden of diagnosing and treating the horse but also of protecting the rider from cases of overwhelming risk. “Sometimes it’s extremely clear,” she says. “The horse may have a large number of VPCs, and we would agree they are not safe to ride. But there are other cases where we can have differing opinions as to whether the horse is safe or not. In those cases, we go back to clearly communicating the risks at hand and ensuring, above all, that this is an informed adult rider that we are discussing the case with. We should not have child riders on these horses who don’t necessarily understand the risk or may not be able to mitigate the situation or get off quickly enough,” she says emphatically. “When I’m doing an exercising ECG, it is on that day in one small window of time. It’s very difficult in some cases to know if we should be rechecking in six months or one year. We try to do our due diligence and look and monitor them as best as we can. Safety for the horse and rider is my top priority.” While some riders may face the diagnosis that their horse is no longer safe to ride in high-level eventing, for instance, horses can be repurposed to ride and even compete in other disciplines if the case specifics allow it.

Taken to Heart

Equine cardiology is a vast world of intricate skills deployed by the specialist veterinarian to diagnose, categorize and treat conditions related to blood flow and heart rhythm. Like so many avenues of equine veterinary medicine, however, it all starts with a horse’s primary-care veterinarian performing a thorough cardiac exam and either clearing the horse as heart-healthy or calling in reinforcements in the form of a board-certified equine internal medicine specialist trained in cardiology. “The first step is that the veterinarian must be listening carefully to the heart. I’d recommend that happen twice per year, maybe more for performance horses,” Dr. Polkes advises. “If we don’t listen, we’ll never know.” It’s these front-line veterinarians who save numerous lives by picking up on even a subtle murmur or arrhythmia and referring the case for further evaluation. “It’s so very important that we make cardiac health a part of the general wellness exam on a regular basis,” Dr. Polkes stresses. “We can’t predict progression, but we can follow horses for years while observing them holding steady or with their condition progressing. We need data to understand and to be able to inform riders to ensure everyone is safe.”

In the end, it’s specialists with a passion for cardiology, like Dr. Amy Polkes, who bring critical knowledge, expertise and passion to an area of veterinary medicine that can have a key impact on rider safety and the health of the animal. “I really love this,” says Dr. Polkes warmly. “I had the very best mentors, and they passed along a passion for cardiology that I’m able to share now with my equine veterinary colleagues, clients and patients. I feel so lucky to get to do what I do every day.”

The Platinum Podcast

To the Heart of the Matter

Join the discussion as renowned equine cardiology specialist Amy Polkes, DVM, DACVIM, talks common equine cardiac conditions, their impact on performance and safety, and how she’s working to increase awareness of cardiac health in equine athletes.

Listen Now